How to build a trillion-dollar company

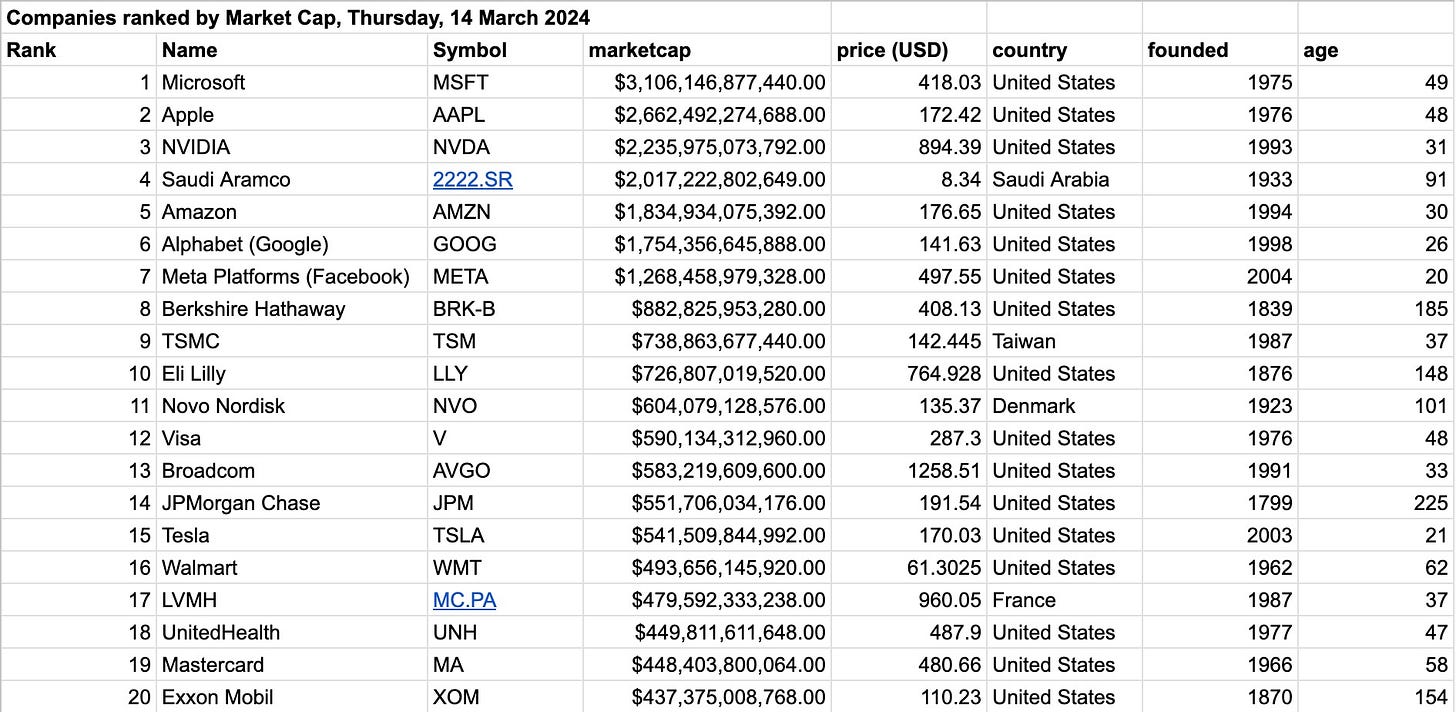

There are a total of seven companies in the world with a market cap of 1 trillion dollars or above.1 Six of those are American, and one is from Saudi Arabia. The most valuable European company is 11th on the list, the Danish Novo Nordisk, with a $600 billion market cap. Why is a single country, the US, so far ahead of everyone else? And how could we build more trillion-dollar companies in the world?

To answer these questions, let’s look at what makes a trillion-dollar company.

Six out of the seven most valuable companies in the world are technology companies. The only non-technology company is Saudi Aramco. The oil and gas industry dominated the top of the list until 2011-2012. Saudi Aramco is almost twice as old as the oldest technology company in the trillion-dollar club. Technology companies seem to be much younger than companies operating in other industries.

What’s more, all the technology companies worth over a trillion dollars were run by their founder until they became one of the largest companies in the world. Microsoft had Bill Gates, Apple had Steve Jobs, Alphabet (Google) had Larry Page and Sergei Brin, Amazon had Jeff Bezos, NVIDIA is still run by Jensen Huang, and Meta (Facebook) is run by Mark Zuckerberg.

What could we learn from this observation?

Technology

Technology has grown out of the technology sector and has become part of every facet of our lives. During the past 15 years, technology has gone from 5% to 15% of global GDP.

The best technology companies will grow bigger and faster because technology reveals new secrets in the world. I expect the ascent to only get faster. Tesla has barely turned 21 and is already one of the world’s most valuable companies.

The United States

All the current trillion-dollar technology companies in the world have been founded and built in the United States. We would do well to study more about why and how the US has acquired the current monopoly on building valuable companies. A lot has been written about the post-war government R&D spending, the large domestic market, and well-functioning capital markets, but it might be even simpler than that. The US is better at attracting a special type of person and amplifying them once in the country.2 These special people are called founders.

The founder

The fact that all the trillion-dollar companies were run by their founder until they practically became global monopolies is surprisingly important if we want to understand what makes a trillion-dollar company.

A founder is a special person. They see a specific future that most others can’t see. The most interesting founders see a world they want to build, not just a business to make money. This matters because you need a definite idea of the future you are building towards if you want to change how the world works. Those only interested in making money can rarely imagine much beyond what they see already existing around them. The best founder-led businesses are valuable for the same reason that the best companies are valued higher than their current revenues: They have ideas about the future that are not yet built out. This vision of the future can’t be delegated to a pool of shareholders, and rarely can it be brought in with a new hire3.

The best founders shape the future to the image of their vision. That’s why nothing is as valuable as a persistent founder with a big vision. Companies without the founder's vision will not know which direction to go. They focus on maximizing short-term profits from their current products because they don’t know what new thing to build. An easy way to spot a company at the beginning of the end is to look at their balance sheet and what they do with their money. If they have a fat balance sheet and mostly use the cash to buy back their shares, they are likely out of ideas about new products to build. They don’t see a future they want to build anymore. A founder is unlikely to sell their business if they have new ideas about what to build, care deeply about them, and have the capital to try. They care more about creating the future they envision than any amount of money they could get by selling the business. A concrete vision is a powerful force in a world where few have any ideas of what the future should look like. The founder is the guardian of that vision.

How to build one?

A founder-led technology company is a good bet if we want to build a trillion-dollar company, but even if it’s a required condition, it’s not sufficient. This is where it gets interesting.

Unfortunately, we can’t build one of the world’s largest companies by deciding to do so. Trillion-dollar companies are created by those following their curiosity or a vision that has grown out of that curiosity, often against a wall of skeptics. Trillion-dollar companies never look like one initially, but when the founder's interest overlaps with the large technological currents impacting the core arteries of our future, giant companies are born.

You can build quite a large company by just wanting to build one—I have seen this happen. But to create a trillion-dollar company, you can’t only be interested in building a large company. You have to be obsessed with the substance, the problem you’re solving for the world; the company is only the vehicle for your vision and determination.

This is probably also why most MBAs and management consultants don’t succeed as startup founders, even though they can be some of the best employees. They are more focused on succeeding than on the substance of their success. Since the trillion-dollar company never looks like one in the beginning, you need to have the persistence to work on ideas that look strange and risky at the outset. An idea that looks like a trillion-dollar company in the early days will never become one since many people can see the same opportunity, and competition will ensure you don’t have the opportunity to build a monopoly. This is why some investors talk about being contrarian right. If you’re only right, the margin gets competed away since everyone else sees the same large opportunity. The best ideas tend to look different, controversial, or downright foolish for their time.4

It’s also the reason why most accelerators fail. They attract people who want to start a company but are less interested in what the company does. This leads them to come up with an idea that looks like it could be a large business but which they are not interested in because of the idea itself.5 I’m guessing Y Combinator’s success has largely come from attracting and identifying people who are, first and foremost, interested in some specific problem but also ambitious enough to build a company around that idea. Teaching the latter is much easier than the former.6 Y Combinator has successfully focused on attracting technical founders and teaching them the business versus the other way around.

The next Bill Gates won’t build Microsoft, and the next Steve Jobs won’t build Apple. Each trillion-dollar company is unique. For all practical purposes, every trillion-dollar company is a monopoly. They get to become so large because they are unique in their own way and different from anything that came before. You can’t follow a playbook when creating something singular. To do that, you need to be comfortable creating something new, and creating anything new is risky because you don’t know what will happen. Your only guide is your curiosity, which can turn into a definite vision of a whole new world if you have the courage to follow it.

This is how the world's most valuable public companies by market cap spelled out on 14 March 2024.

This is not to say that structural issues, policy, and regulation don’t matter. They do, and unfortunately, Europe is badly failing. All these issues become impediments to attracting and amplifying founders, without whom we don’t have any new companies, let alone ones worth trillions of dollars.

Microsoft, currently the most valuable company in the world, might be an example of such an exception where Satya Nadella is building the future with a founder-like ownership and zeal.

The challenge for investors is that most ideas that look different, controversial, or downright foolish are all those things. The trick is to know which ideas are only that and which the right founders can build into valuable companies.

Sometimes the most interesting companies are born from a question the founder has instead of an answer. The idea for a company emerges when you try to answer the question.

Really like your writing Ville - sharp pen, sharp mind!